This article explores the rhetorical and legal strategies used to critique, regulate, and shut down so-called sex robot brothels across Asia, Europe, and North America from 2004 to 2024. Through an analysis of media narratives, the piece reveals how various figures—sex dolls, sex robots, sex workers, and trafficked individuals—are often conflated and framed as subhuman entities posing a threat to public morality and safety. Drawing from queer theory, critical race studies, and inhumanist critiques of sexuality and technology, the article examines how these narratives are deeply informed by Eurocentric humanist ideals and techno-Orientalist assumptions. In particular, it highlights how Asian sex workers are positioned simultaneously as victims and dehumanized objects, often likened to robots themselves. Through the case study of Berlin-based Cybrothel and its unique “Analogue AI” model, this article proposes that sex doll and sex robot brothels might offer new forms of intimacy and living that challenge normative understandings of sexuality, embodiment, and personhood.

Keywords

Sex robots, sex work, artificial intelligence, municipal law, techno-Orientalism, queer inhumanism

Introduction: Loving the Machine

Queer theorist Michael Warner once argued that sexual autonomy has long been shaped by technological innovation—razors, lubricants, hormones, and Viagra have all transformed how we engage with sex and our own bodies (Warner 1999). Fast forward 25 years, and the landscape of sexual technology has only expanded. Synthetic skin, virtual reality, haptic interfaces, and artificial intelligence are now integral to emerging sexual cultures. Notably, in 2023, Pornhub reported a surge in search terms like “android,” “sex robot,” and “AI robot,” indicating a growing curiosity about machinic intimacy (Pornhub 2023). Indeed, we are in a cultural moment where sex robots have captured the public imagination.

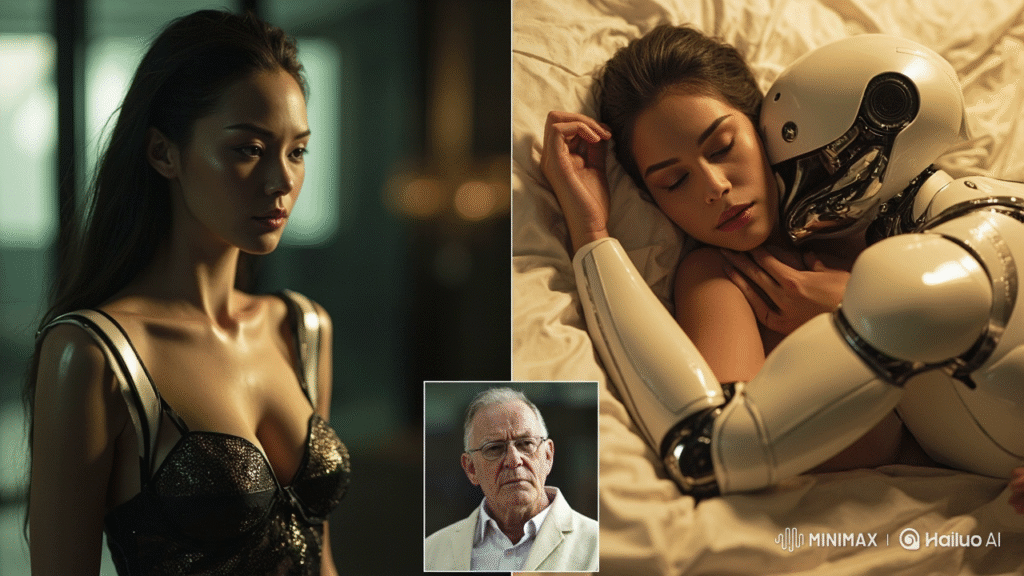

Despite this, what are often called “sex robot brothels” rarely involve actual AI-powered robots. These establishments typically rent out hyper-realistic silicone dolls but not functioning sex robots with AI. Moreover, many of these businesses—despite the brothel label—do not employ human sex workers. One exception is Cybrothel in Berlin, which launched in 2020 and offers a hybrid experience called “Analogue AI.” Here, customers rent synthetic dolls, which are brought to life through remote interactions with real sex workers and voice actresses via embedded cameras and speakers (Culley 2023; Hanson & Smith 2024).

This article interrogates how such spaces have been scrutinized, often shut down, and heavily regulated. It investigates the legal rhetoric and cultural fears underlying this regulation, specifically how these fears draw from colonial ideas about race, gender, and technology.

Sex Robots as Subhuman Threats

Media and legal discourses frequently conflate sex dolls, AI robots, trafficked persons, and sex workers into a monolithic figure of deviance. These figures are constructed as subhuman, dangerous, and in need of control. This framing intersects with a broader cultural fear around the erosion of “human” values in the face of technological advancement. The sex robot becomes a symbolic figure—one that threatens not only traditional sexual norms but also conceptions of what it means to be human.

Drawing from queer inhumanist frameworks, this article argues that the very idea of the “sex robot brothel” forces us to confront how the line between human and non-human is racialized, gendered, and sexualized. Particularly telling is the repeated portrayal of Asian sex workers as robotic, submissive, or in some cases, indistinguishable from the dolls themselves. These portrayals echo long-standing techno-Orientalist tropes, which render Asian bodies as laboring machines—silent, efficient, and lacking subjectivity (Morley & Robins 1995; Eng, Ruskola, & Shen 2011).

Asian Sexuality and the Limits of Eurocentric Humanism

Rather than striving to “rehumanize” Asian sex workers by separating them from robots, this article invites us to consider what possibilities emerge when Asian sexual subjects lean into the robotic. In doing so, they disrupt the binary logic that separates the human from the non-human, the real from the artificial, and the intimate from the mechanical.

This perspective is informed by a growing body of queer and posthumanist scholarship that refuses the imperative to reclaim humanity as the only path to dignity or rights (Luciano & Chen 2015). From this angle, the sex robot and its adjacent technologies may not represent a fall from authentic human intimacy, but rather a new terrain for imagining pleasure, agency, and embodiment.

Case Study: Cybrothel and the ‘Analogue AI’ Experience

Cybrothel provides a compelling counter-narrative to mainstream fears. With its “Analogue AI” model, the company merges synthetic physicality with human interaction. While the dolls themselves are not truly robotic, they are animated by real human workers—voice actresses and sex workers—who guide and shape the customer’s experience in real time. This hybrid model challenges the dominant binary between sex worker and sex object, suggesting instead a collaborative assemblage of technology and human labor.

Far from dehumanizing, Cybrothel’s model reveals how machinic interfaces can be harnessed to extend human intimacy and craft new kinds of relationality. Rather than viewing the robot as a threat to human connection, this model posits that robots—when used creatively and consensually—can enhance affective experiences and broaden the scope of intimate life.

Conclusion: The Future of Intimacy

Sex robot brothels have become flashpoints in debates about morality, legality, and the future of human relationships. However, the outrage they provoke is often rooted not in the reality of what they are, but in the symbolic disruptions they represent. They challenge the stability of categories such as human/non-human, sex/labor, subject/object, and East/West.

This article has shown that fears surrounding sex robot brothels are deeply racialized and gendered, relying on entrenched techno-Orientalist narratives and anxieties about losing control over sexuality and subjectivity. Yet, in turning toward the robot—and away from the narrow, Eurocentric ideal of the human—there lies the potential for more expansive, inclusive, and liberatory sexual futures. Sex robots and their affiliated spaces may not destroy intimacy; they may help us imagine it anew.

Leave a Reply